One of the best things about running asylumscience is the queries that we receive about the history of psychiatry. Simon Tombs, teacher of Psychology at Devonport High School for Girls in Plymouth, recently contacted us about a project he was putting together on King George III. In this guest post, he tells us more.

At Devonport High School, we have a long tradition of working with schools from other countries on projects that promote international understanding. Last October, I was offered the chance to work on a project with the Käthe-Kollwitz-Schule in Hanover. The English participants were Year 9 students (13-14 year olds), the German students a year older. The plan was for the German students to come to Plymouth in June 2013 and the Plymouth students to Germany the following year. The working title for the project was ‘History Matters’ and the springboard for this European-funded partnership is the 300th anniversary (in 2014) of the accession of the Hanoverians to the British throne. There were a number of topics planned for the project. George III’s madness was one of them. We aimed to understand something about how ideas about mental health and illness were exchanged between England and Germany. A bit of internet research suggested that psychology and psychiatry as academic disciplines started around the time of George’s illness in Germany. We wondered how, if at all, these ideas might have affected his treatment and recovery. For this project, I worked principally with Gesa Wrage at the Käthe-Kollwitz-Schule, and Elspeth Wiltshire who co-ordinates international projects at Devonport.

The original plan was to devise a session called ‘Out Of Sight, Out Of Mind’. I got in touch with Jennifer at asylumscience. She was able to provide some leads about asylums in the early 19th century. I had a look at an account of life inside the Eberbach Asylum in Germany and a summary of what German doctors had discovered when they visited England in the mid-19th century. This seemed promising: we could show students images of asylums from both Britain and Germany and ask them to consider what was the same or different. The written sources might tell us something about what life was like. We could think about why people living with mental illness might be moved to the countryside. I found something about the debate between ‘somaticists’ and ‘psychisists’ whose ideas about the causes of mental illness seemed to prefigure current debates on biological and psychological explanations for mental disorders.

The original plan was to devise a session called ‘Out Of Sight, Out Of Mind’. I got in touch with Jennifer at asylumscience. She was able to provide some leads about asylums in the early 19th century. I had a look at an account of life inside the Eberbach Asylum in Germany and a summary of what German doctors had discovered when they visited England in the mid-19th century. This seemed promising: we could show students images of asylums from both Britain and Germany and ask them to consider what was the same or different. The written sources might tell us something about what life was like. We could think about why people living with mental illness might be moved to the countryside. I found something about the debate between ‘somaticists’ and ‘psychisists’ whose ideas about the causes of mental illness seemed to prefigure current debates on biological and psychological explanations for mental disorders.

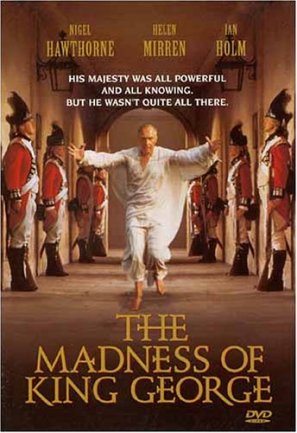

The Madness of King George

One of the experiences which transformed the project was watching The Madness of King George. I had a vague recollection of seeing the film when it was released almost 20 years ago, and remembered the brutality of some of the treatments given to George. I also remembered Alan Bennett having fun with the depiction of Francis Willis, the doctor who was thought to have cured George, as a dour Lincolnshire puritan (my wife is from Lincolnshire). I realised when I watched the film again how many powerful ideas were in it. George’s illness was public knowledge and was seen as everybody’s business, in part because of the political situation at the time. In this, he seemed to prefigure modern celebrities who go public about their mental health.

One of the experiences which transformed the project was watching The Madness of King George. I had a vague recollection of seeing the film when it was released almost 20 years ago, and remembered the brutality of some of the treatments given to George. I also remembered Alan Bennett having fun with the depiction of Francis Willis, the doctor who was thought to have cured George, as a dour Lincolnshire puritan (my wife is from Lincolnshire). I realised when I watched the film again how many powerful ideas were in it. George’s illness was public knowledge and was seen as everybody’s business, in part because of the political situation at the time. In this, he seemed to prefigure modern celebrities who go public about their mental health.

I also caught an excerpt of Simon Schama speaking at the Hay Sessions, discussing the importance of the late 18th century in our view of the modern world. Schama was bemoaning the lack of emphasis placed on this period in the new National Curriculum for History. I realised that George’s story stood at the point at which people began to realise that mental illness was something that could be understood scientifically. Francis Willis may have lacked social graces but he was at the forefront of enlightened, scientific thinking. He was part of a broader movement for change in England, Germany, and elsewhere in Europe. He became a celebrity after George’s recovery, receiving a generous state pension, a series of portraits and a special commemorative coin. Willis believed that George could get better. With this in mind, we planned for the students to watch The Madness of King George before their visit. I put together a session for the students to look at sources and understand more of the background to George’s story.

Discussing taboo

The second transforming experience was getting some help from a small group of the German students. They had been to an exhibition about taboo at an art gallery in Hanover and made a 10-minute Powerpoint presentation about what they had seen. They explained the origins of the word ‘taboo’, what was seen as taboo in the 18th century, and what was taboo today. Their presentation raised some important questions. They made a connection between taboo and religion and made me think more fundamentally about where the stigma around mental illness really comes from. We used their input to discuss some questions:

- Should we be talking about what was wrong with someone who died a long time ago and is not here to speak for himself?

- If someone famous or important today has a mental illness, do we have the right to know about it?

- Should celebrities living with mental illness talk about their illness? Should journalists write about it?

- Is there still a taboo about mental illness? If there is, who makes it a taboo?

- Apart from celebrities, should the views and opinions of people living with mental illness be heard more?

Mind’s Time to Change campaign has tried to break taboos around mental illness, with celebrities like Stephen Fry talking about their experiences.

Visiting Saltram House

The third part of the project was a visit to Saltram House, a National Trust property on the edge of Plymouth. With the support of Anida Rayfield, who leads the volunteer tour guides at Saltram, we found that George had stayed there for a fortnight in 1789 following his illness. The house still looks very much as it did when George was there. George’s visit was designed to show that he had recovered. The route of his journey from Weymouth was lined with well-wishers, he came into Plymouth to great public acclaim to review the fleet, and visited the houses of the local gentry. We started to wonder how well he really was and if his visit was a form of convalescence. The family who lived there and all but two of their staff were absent throughout his stay: George brought his own people with him. He was able to walk in the extensive grounds in what was then a rural setting. His staff and carers would have been able to establish a routine and keep things in the manner to which he was accustomed. There was no court business conducted during his stay. It looks as if his stay in Saltram exemplified the ‘moral treatment’ advocated by Francis Willis and others.

Students imagine how a modern newsreader might report George III’s visit to Saltram House. © Elspeth Wiltshire/Simon Tombs.

Outcomes and going forward

Our project is ongoing. At the end of their session, we asked students why they thought the madness of King George was important and what else they wanted to know. Some focused on historical questions about what happened next, others said they wanted to know more about the idea of taboo. Others raised questions about science and medicine, both in relation to what was wrong with George and how he was treated, and with regard to what is done for people who suffer from conditions like George’s today. Both English and German students had the opportunity on the final day of the visit to explain what some of these questions were in a presentation to an invited audience of students, parents, and others connected with the school and the project. We have a year to work out how to deal with these questions and share ideas before the English students visit Germany in 2014.

For me, it has already become clear why the madness of King George III matters. Through his story, we can see the birth of ideas that we deal with in contemporary psychology. We can see how questions about taboo, historical diagnosis, and the voices of people living with mental illness emerge from his story. One of the things we have not yet got hold of is what George himself thought of how he was treated, both at Saltram and before and after his visit there. I hope that is something we will understand better in time. Before we started, we were concerned that we were exposing some of the younger students to material about mental illness which they might find difficult. To deal with this, we formulated a statement that set boundaries and explained where support might be found. History matters because it enables us to approach issues which we might have forgotten, or feel embarrassed by. The sources about George in the form of written accounts, images and – in the case of Saltram House – concrete objects give us a vivid and compelling insight into these issues. We finished our session by watching a scene towards the end of The Madness of King George. George acts out the scene from King Lear where Lear is reconciled with Cordelia and talks about himself and his illness. I know of no better portrayal of the pain, the resilience, and the hope that are at the core of the experience of people who live with mental illness.

For me, it has already become clear why the madness of King George III matters. Through his story, we can see the birth of ideas that we deal with in contemporary psychology. We can see how questions about taboo, historical diagnosis, and the voices of people living with mental illness emerge from his story. One of the things we have not yet got hold of is what George himself thought of how he was treated, both at Saltram and before and after his visit there. I hope that is something we will understand better in time. Before we started, we were concerned that we were exposing some of the younger students to material about mental illness which they might find difficult. To deal with this, we formulated a statement that set boundaries and explained where support might be found. History matters because it enables us to approach issues which we might have forgotten, or feel embarrassed by. The sources about George in the form of written accounts, images and – in the case of Saltram House – concrete objects give us a vivid and compelling insight into these issues. We finished our session by watching a scene towards the end of The Madness of King George. George acts out the scene from King Lear where Lear is reconciled with Cordelia and talks about himself and his illness. I know of no better portrayal of the pain, the resilience, and the hope that are at the core of the experience of people who live with mental illness.